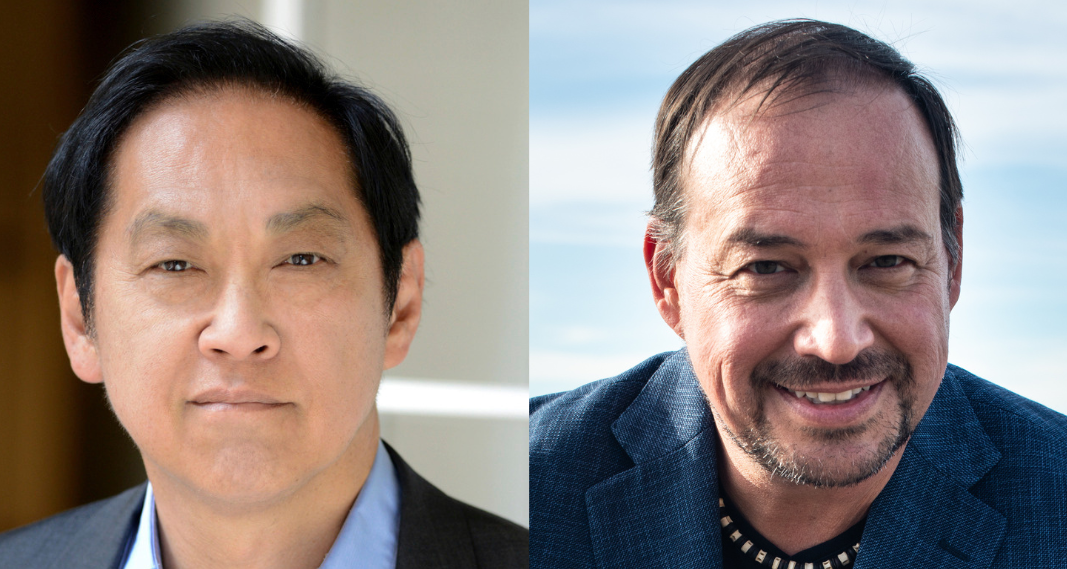

Yota Kobayashi explores the nature of perception and reality in Shiki & Kū

The locally based soundscape artist and his global collaborators have crafted an immersive experience at VIVO Media Arts Centre, with Formscape Arts, Vancouver New Music, and IM4 Media Lab

Still shot of Shiki & Kū.

Still shot of Shiki & Kū.

Formscape Arts Society and VIVO Media Arts present Shiki & Kū at VIVO Media Arts Centre from September 13 to 28, with Vancouver New Music and IM4 Media Lab

TO FULLY GET A handle on the concepts at play in Yota Kobayashi’s installation Shiki & Kū, it might help to start with a definition of the title. Then again, it could be better to just let the experience wash over you, with no preconceived notions of what it all means.

In any case, when Stir connects with Kobayashi, the Vancouver-based soundscape artist is only too happy to define shiki.

“It could mean, in English, form, or tangible reality,” he explains. “Things that you can recognize—say, a chair that you can sit on, a tree that you can see, sounds that you can hear, love that you can feel, touch that you can experience. Something like that.

“And then kū, on the other hand, that means emptiness,” Kobayashi continues. “That’s the only word I could find in the English language. But it doesn’t mean nothingness or nothing. Instead, it means that those realities, like shiki, they’re all impermanent. The realities can exist only through imagination, as they are discerned.”

Students of Zen Buddhism might recognize this idea as one expressed in the Heart Sutra as “Shiki soku ze kū, kū soku ze shiki.” A Western spin on it might be that reality is in the eye of the beholder. (Alternatively, a glass-half-empty type may relate more to Arthur Schopenhauer’s pessimistic take on things: “Every man takes the limits of his own field of vision for the limits of the world.”)

Shiki & Kū actually consists of two separate but related works, each an immersive audiovisual installation. Kūsou, previously seen at Anvil Centre in 2022 as part of the Powell Street Festival, consisted of large-scale projections of Japanese kanji, lyrically realized by calligrapher Aiko Hatanaka, set to Western classical flute phrases played by Vancouver musician Mark Takeshi McGregor. Through Kobayashi’s sonic design and the visual programming of Ryo Kanda, these basic elements are transformed into an ever-shifting and endlessly mesmerizing tapestry of sound, light, and colour.

The brand new piece Shinshiki, meanwhile, weaves a similar spell with music from the Italian string quartet Quartetto Maurice and visual symbolism drawn from the Japanese tradition of animism.

Kobayashi explains that Shinshiki is rooted in the ancient concept known as Yaoyorozu no Kami, which translates as “8 million divinities”. In the animistic Shinto religion, these divinities, or kami, can be anything from mythological beings to natural phenomena to the spirits of long-deceased ancestors.

As Kobayashi explains on his website, “In the ancient Japanese worldview, there is no absolute kami to which all others are subordinate; rather, all kami coexist and evolve harmoniously, permeating the entire cosmos.”

These manifestations of the divine keep nature in balance, and are said to be present in, well, pretty much everything—so don’t take that number literally.

“Eight million here means infinite, so a countless number of divinities coexist in nature, because all things in nature host divinities, but they don’t fight each other,” Kobayashi says. “So it’s quite a peaceful idea, which was quite influential in Japan, even before Buddhism and other religions were imported to Japan, so it could be 2,000 years ago.”

These traditional beliefs are the foundation upon which Kobayashi and his Formscape Arts Society collaborators built Shinshiki, but the soundscape artist points out that there is no narrative for viewers to follow, and that the installation’s sensory immersion conveys no specific message to its audience. Instead, computer graphics bring the visual elements of Shinshiki to life as 3D objects and events—a forest, flocks of birds, a solar eclipse—shaping a continuously evolving exhibit space.

The emergent theme of harmonious coexistence will likely resonate with many viewers, possibly even inspiring them to reflect on, as the project’s online description says, “the potential for unity amidst the divisions that shape our world”. That’s one possible interpretation, at any rate.

“There is no big story,” Kobayashi insists. “There are no things that we represent and then force on their imagination. So, basically, the artwork is not expressing. We are only representing scenery where the audience can create realities unique to themselves through their imagination.”

This, again, comes down to the notion that reality is fluid and subjective, and that our perceptions shape our experiences—and vice versa.

“A chair, that you can think is a chair, may not be a chair for a baby, right?” Kobayashi says. “It’s just a gigantic wooden object, for someone who is small. For example, love between two people: one of the partners may think that there is a love between the couple, but the other may not think that that’s existing. So, you know, things may exist, but only uniquely to yourself.

“The world exists and this universe is composed of unique realities from individual imagination, experience, perception,” the artist concludes. “But the bottom line is that there is only an ocean of possibilities from which we individually can realize those realities together.” ![]()